The updated 2026 Food Pyramid (also known as the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2025–2030)) has reignited a national conversation about what “healthy eating” actually looks like and what should be recommended to the public at a federal level.

The Dietary Guidelines are jointly developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). They shape federal nutrition policy, from school meals to public health messaging to what you see repeated across media headlines.

From my point of view, some of the messaging in the updated guidelines is helpful, especially the continued focus on whole foods and limiting highly processed foods and added sugars. That’s not a “brand new” message (and it shouldn’t be treated as one), but it is a positive reinforcement of what we’ve known for a long time.

At the same time, I have concerns.

The pyramid-style model can be misleading, and some of the emphasis in these new recommendations may create confusion, especially for everyday Americans who just want to feel better, manage their weight, improve their heart health, or understand what to eat without turning meals into a math problem.

Why this matters (more than people realize)

These guidelines influence:

- what kids are served in schools

- what registered dietitians, doctors and healthcare systems reinforce

- what nutrition trends take off in mainstream media

- and what the average person believes they “should” be eating

That’s why it’s important to look at these recommendations with both openness and a critical eye.

What I’ll cover in this post

In this article, I’m going to break down:

- what changed in the 2025–2030 Dietary Guidelines

- what I believe is helpful and worth keeping

- what worries me most (excessive protein, saturated fat, and an inadequate emphasis on grains and vegetables)

- and what I recommend instead

Growing up in Canada, dietitians came into our classrooms and taught us about food and what was healthy. I believe that’s a big piece of what’s missing in the U.S. nutrition education system today. Telling people what to eat is one thing. Teaching them how to build a balanced diet they can actually sustain is another.

What Changed in the Updated Food Guide Pyramid

Big-picture shift: “eat real food” emphasis and less ultra-processed

One of the biggest takeaways from the updated guidelines is a renewed focus on what I’ll call common sense nutrition: eat real food more often, and cut back on heavily processed options.

But I want to be clear. This idea isn’t new.

If you’ve read previous versions of the Dietary Guidelines, the core message has consistently been centered around healthy meals that include fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins, while limiting added sugars and overly processed foods.

For example, even back in the 2005 Dietary Guidelines, the emphasis was already on choosing fiber-rich fruits, vegetables, and whole grains and limiting added sugars.

So yes, I do think the direction is positive. But it’s not a sudden breakthrough in modern nutrition science as much as it is a re-packaging of what we’ve known and been told for a long time, minus the confusing pyramid.

What does “ultra-processed” mean?

Ultra-processed foods tend to be products that are:

- packaged and ready-to-eat

- made with multiple additives and preservatives

- high in added sugars and/or sodium

- low in fiber

This is also where we commonly see a lot of refined carbohydrates such as foods made with white flour and added sugars that don’t keep you full for long, don’t support gut health, and don’t offer much nutritional value.

That said, I want to be careful here: not all processed foods are bad.

Frozen vegetables, canned beans, bagged salad kits are great food choices that can make healthy eating easier and more accessible. The goal shouldn’t be to eliminate entire categories of food or create fear. It should be to build a pattern that’s realistic and sustainable.

Increased protein targets (1.2–1.6 g/kg/day)

The updated guidelines also recommend a higher protein intake: 1.2 to 1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day. That’s a major increase from prior minimum recommendations and it’s one of the most talked-about changes.

For certain people, that amount can be appropriate but for many adults, it may be unnecessary and difficult to maintain without crowding out other important foods.

If you want a deeper breakdown on protein needs (and what those numbers look like in meals), I wrote about that here.

The pyramid visually pushes animal-based foods higher

This is where the guidelines are confusing.

When you use a pyramid-style mode that isn’t clear, people don’t read the fine print, they follow what the visual shows and that is misleading.

If the graphic highlights certain major food groups more heavily (especially animal-based proteins and higher-fat dairy), the public will probably interpret that as “eat more of these foods,” even if the guidelines simultaneously recommend limiting saturated fat (which unfortunately contradicts the visual). This is confusing, therefore higher saturated foods like meat and full-fat dairy, should not be at the top of the pyramid.

Experts have also raised concerns that the pyramid will be used to justify higher intakes of red meat and dairy in a way that isn’t ideal for heart health or for the planet.

What I like about the updated guidelines

Even with my concerns, there are things I appreciate:

- Less added sugar (and more direct attention on reducing it)

- More emphasis on whole foods which includes fruits and vegetables.

- Reducing processed foods in the American diet

I’m glad we are continuing to encourage more whole foods. We just need to be careful that the messaging remains balanced and supports an eating pattern that helps people eat well without confusion, guilt or unnecessary restriction.

The Big Problem: The Pyramid Model Confuses People

Why the food pyramid format is flawed

Here’s the issue with any food pyramid (including this updated one): it looks simple… but it often teaches the wrong lesson.

A pyramid doesn’t just show categories of food, it visually communicates priority. The wide section sends a clear message to the average reader:

“Eat more of this.”

And that’s where things start to go sideways.

When the widest section is packed with animal-based foods like meat and full-fat dairy, many people will interpret that as permission to load up, even if they’re already eating plenty of those foods.

Nutrition doesn’t work well in extremes.

We don’t want people overeating any one group, because that’s how we end up with nutrient gaps, unbalanced diets, and higher risk for chronic disease over time.

The goal of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans is to help people eat in a way that supports long-term health, not to push “more” of one category while other categories get squeezed out.

Here’s what happens in real life:

If someone over-focuses on protein and animal fat, they often end up eating fewer nutritious foods like:

- vegetables and fruit

- beans and lentils

- whole grains

- nuts and seeds

Those foods are categorized as nutrient-dense foods (high-quality foods). They give you more fiber, vitamins, minerals, and protective compounds per bite.

And they’re also where we naturally get more healthy fats, including essential fatty acids (like omega-3s), which are important for heart and brain health. These fats are found in foods like fatty fish (salmon, sardines), chia seeds, flaxseed, walnuts, and some plant oils, not butter, tallow, or processed meats.

My concern is that the pyramid format doesn’t communicate balance very well. It pushes people toward an “eat more of what’s featured” mindset when the ideal solution is variety, proportion, and consistency.

You shouldn’t eat too much of ANYTHING.

Why visuals matter

Most people don’t read nutrition guidelines like a textbook. They glance. They scroll. They see a picture and assume they understand it.

That’s exactly why visuals matter.

A pyramid graphic can override the nuance that’s written in the actual text, especially when the messaging is conflicting.

For example, the guidelines can say “Limit saturated fat” but the visual shows “Eat more animal fat and full-fat dairy”.

This is why I personally prefer tools like MyPlate (which we’ll get to later). They make balance easier to understand at a glance, without pushing extremes.

Bottom line: The visual format and arrangement of foods on the food pyramid contradicts the written Dietary Guidelines and misunderstanding nutrition guidance is exactly how we stay stuck in cycles of confusion, frustration, and preventable chronic disease. The pyramid should have pictures of beans, nuts and fish at the top, but it doesn’t.

If we truly want healthier outcomes, we need clear guidance that helps the average person make choices that are realistic, balanced, and sustainable, without turning nutrition into a trend or an all-or-nothing rulebook.

Concern #1. Saturated Fat Contradictions (and Heart Health Risk)

This is one of the biggest issues I see with the updated food pyramid: the message is mixed.

On one hand, dietary guidelines still encourage a heart-healthy approach. On the other, the pyramid’s visual emphasis promotes more foods that promote a higher saturated fat intake.

When we’re talking about national nutrition policy, clarity matters.

People want a common sense message that supports a healthy lifestyle and reduces risk of heart problems long-term. The visual presented needs to align with the written guidelines, which it does not.

The guidelines still say: keep saturated fat under 10%

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends keeping saturated fat to less than 10% of total daily calories. For someone eating around 2,000 calories per day, that’s roughly 20 grams of saturated fat.

So what does saturated fat have to do with heart health?

When a diet is consistently high in saturated fat, it can raise LDL cholesterol (often called “bad cholesterol”), which increases risk for cardiovascular disease, meaning things like heart attacks and stroke.

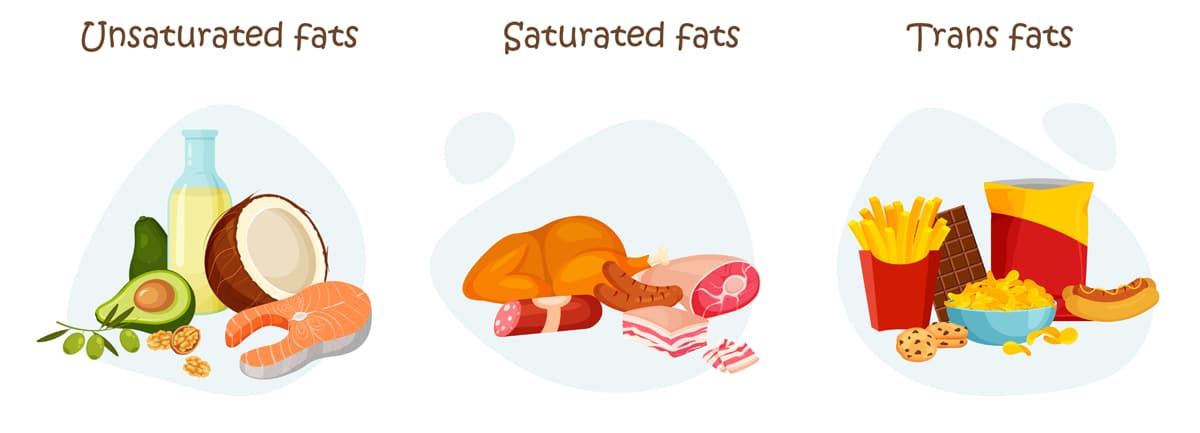

This is why organizations like the American Heart Association strongly recommend limiting saturated fat and prioritizing unsaturated fats instead.

The pyramid promotes foods that can push saturated fat too high

The food pyramid places heavy emphasis on foods like:

- red meat

- full-fat dairy products

- butter

- beef tallow

It’s hard to say “eat less saturated fat” while encouraging an eating style that leans heavily on animal fats.

To me, that starts to challenge the scientific integrity of the message because the recommendations and the pyramid visual are not aligned.

A quick note about the original pyramid (and why this matters)

Historically, the USDA Food Guide Pyramid included five major food groups:

grains, fruits, vegetables, dairy, and protein.

That’s part of why the current shift feels like such a significant reset. It changes what people perceive as the “main focus” of a healthy diet.

What I would rather see recommended

If we want guidance that supports heart health, we should be emphasizing healthy fats more consistently, especially fats that support the body without pushing saturated fat intake sky high.

What I’d love to see in the recommendations for healthy fats:

- olive oil

- avocado oil

- nuts and seeds

- fatty fish (like salmon)

- more plant-based fats overall

These options support heart health and also provide important nutrients, including essential fatty acids that the body cannot make on its own.

This is what I recommend to all of my clients.

Common saturated fat sources + simple swaps

These swaps can make a big difference, without giving up flavor or feeling deprived.

- Butter → olive oil (cooking) or olive oil-based spread (toast)

- Beef tallow / lard → avocado oil (high-heat cooking) or olive oil (medium heat)

- Fatty red meat (ribeye, burgers, sausage) → leaner cuts (sirloin, 90–93% lean ground beef) or poultry/fish

- Bacon / processed meats → turkey bacon (occasionally) or unprocessed proteins (eggs, beans, chicken)

- Whole milk → 2% or 1% milk

- Full-fat cheese → reduced-fat cheese or keep full-fat but use less

- Heavy cream → half-and-half, evaporated milk, or plain Greek yogurt (for creamy sauces)

- Coconut oil (high saturated fat) → olive oil or avocado oil

- Ice cream / pastries → smaller portion + more intentional frequency, or Greek yogurt + fruit as a regular option

You can absolutely eat whole food and still choose fats that better support long-term heart health.

That’s what balanced nutrition looks like and it’s what we should be promoting through national guidelines.

Concern #2. The Protein Push Is Too Much for Most People

Yes, protein matters. It helps with muscle health, blood sugar stability, and feeling satisfied after meals. But the way this is being emphasized in the updated food guide pyramid risks turning protein into the “main event” of every meal and for most people, that’s not necessary (or realistic).

If the goal of the United States Department of Agriculture and Health agencies is to help Americans build a sustainable, long-term way of eating, this is where the message starts to lose me, especially when we’re talking about reducing chronic disease risk, not bodybuilding.

Individuals who need (or benefit from) more protein

There are people who truly need more protein than average. Examples include:

- Athletes or anyone doing regular strength training

- Older adults trying to preserve lean mass (muscle naturally declines with age)

- People with specific medical needs (depending on diagnosis and under medical guidance)

- Pregnant and postpartum women (higher nutrient demands)

The key word here is individualization.

Protein needs depend on your body, age, goals, health history, and physical activity level. A one-size-fits-all number doesn’t make sense.

Why it’s unrealistic (and potentially counterproductive)

For everyday people, a very high-protein target can backfire.

Why?

Because protein is extremely filling.

If you’re trying to hit 1.2–1.6 g/kg/day, you may get so full from protein-heavy meals that you crowd out other foods your body needs, especially:

- fruits and vegetables

- whole grains

- legumes

This matters because fiber, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants don’t come from protein foods alone.

So yes, you might be eating “real food” but you could still end up with a diet that’s less balanced and less nourishing.

This is why I often tell clients that most everyday people do not need this much daily protein. I rarely recommend over 1.0–1.2 g/kg unless there’s a reason.

What’s missing: quality and variety of protein sources

Another concern I have with the way this is being presented is that it risks putting too many foods in the same category, as if all protein sources have the same health impact.

They don’t.

A smarter message would focus on protein quality and variety, such as:

- more plant proteins (beans, lentils, tofu/tempeh, nuts, seeds)

- more seafood

- dairy in moderate amounts

If we want guidance rooted in modern nutrition science, that’s the approach that aligns best with what we know: more variety, more plants, more fiber, and less reliance on animal-heavy eating patterns.

If we’re being honest, many high-protein packaged foods are still highly-processed foods. So “high protein” does not automatically mean “healthy.”

How much protein do you need?

For most adults, a very reasonable target is:

- ~1.0 g/kg/day (simple, practical, sustainable)

Higher protein ranges (1.2–1.6 g/kg/day) are usually reserved for:

- muscle gain or heavy training

- older adults preserving muscle

- pregnancy and postpartum

- certain medical situations (with individualized guidance)

If you want a deeper breakdown, I explain this in plain English here:

https://mynutritiondesign.com/how-much-protein-does-a-woman-need

Step 1: Convert your weight to kilograms

lbs ÷ 2.2 = kg

Examples:

- 140 lb → 64 kg

- 160 lb → 73 kg

- 180 lb → 82 kg

What does “60–80g/day” look like in actual food?

Here’s a sample day that lands around 64–69g, which is a realistic and balanced range for many adults:

- Greek yogurt (1 cup): ~18g

- 2 eggs: ~12g

- Chicken (3–4 oz): ~25–30g

- ½ cup lentils: ~9g

Total: ~64–69g

Simple guideline (no protein math required)

Instead of obsessing over grams, try this:

- Aim for 20–30g protein per meal

- Add 10–15g from snacks if needed

That lands most people in a healthy range without turning every meal into a numbers game.

In my opinion, if nutrition advice makes eating feel like a math test, it’s no longer helping people eat healthier.

Concern #3. Protein Sources Should Be More Plant-Forward

This is where I think the new pyramid misses a big opportunity.

If we’re going to encourage people to “eat better,” it’s not enough to just push more protein. We also need to talk about where that protein is coming from because protein sources are not all equal when it comes to heart health, digestion, and long-term wellbeing.

Health: Plant proteins come with fiber + phytonutrients

One of the main reasons I recommend a more plant-forward approach is that plant proteins come with benefits animal proteins don’t.

Foods like:

- beans and lentils

- tofu and tempeh

- nuts and seeds

- and even vegetables like dark green vegetables

…don’t just provide protein. They also provide:

- fiber (which helps with digestion, blood sugar, and cholesterol)

- antioxidants and phytonutrients

- key vitamins and minerals

That’s one of the reasons I’d love to see a stronger emphasis on fruits and vegetables, not only for vitamins, but because they support heart health in a way the average American diet desperately needs.

To be clear: a small amount of lean animal protein, especially grass-fed beef can be part of a healthy diet. But it shouldn’t dominate the plate the way many people would interpret it from a pyramid graphic, especially when it crowds out the foods that help protect us long-term.

When you make plant foods the foundation, you naturally get more of the things most Americans need to significantly reduce chronic health risk: more fiber, more nutrients, and more balance.

Sustainability: More cattle/livestock = more greenhouse gas emissions

Raising cattle and livestock contributes to greenhouse gas emissions. For example, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency explains that agriculture accounts for a meaningful share of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

That’s why many nutrition experts are concerned that a meat-forward message isn’t just an issue for health, it can also be a problem for the planet.

Dr. Walter Willett, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (and one of the most cited nutrition researchers globally), warned that these updated recommendations could be used to promote higher intakes of red meat and dairy “which will not lead to optimally healthy diets or a healthy planet.”

I think that’s worth taking seriously.

Why the way this is framed matters (and what’s being removed)

RFK’s pyramid is being described as a major shift away from “all foods fit.” It focuses heavily on protein and dairy, while including fruits, vegetables, and “healthy fats”. It also removes many ultra-processed foods. That includes soda, chips, cookies, and ice cream and some everyday staples like breakfast cereal, soymilk, and canned vegetables.

I completely support limiting ultra-processed foods most of the time but I don’t believe the answer is making nutrition feel like a “pass/fail” test.

In real life, people need guidance that supports:

- balance

- flexibility

- and practical choices that work in different lifestyles and budgets

Not everyone has access to farmers markets, specialty food stores, or time to cook from scratch daily.

My bottom line: if we want guidelines that support health, we should be promoting protein in a way that encourages more plant-forward choices, more variety, and a stronger foundation of fruits and vegetables, including nutrient-rich options like dark green vegetables.

Concern #4. The Grain Guidance Is Too Low (and Risks Backfiring)

When you visually shrink grains down to a small, “almost optional” role, a lot of people will read that as:

“Carbs are bad. I should avoid them.”

Carbs are not the enemy and in my experience, when people slash grains too hard, it often backfires.

Whole grains provide key fiber and nutrients

Let’s start with the basics: your body needs carbohydrates.

Carbs are your body’s easiest source of energy, especially for your brain and muscles. When those carbs come from whole grains, you’re not just getting energy, you’re also getting fiber, which is one of the most overlooked parts of a balanced diet.

Whole grains are one of the biggest sources of fiber in the average diet. Fiber helps support:

- stable blood sugar

- fullness and appetite control

- gut health (regular bowel movements + better digestion)

- lower LDL cholesterol (the “bad” cholesterol)

The USDA’s own MyPlate guidance explains that fiber from whole grains may help reduce blood cholesterol and lower heart disease risk. The American Heart Association also highlights fiber’s role in digestion, blood sugar control, cholesterol lowering, and fullness.

Why less grains can backfire in real life

In theory, some people think: “If I eat fewer grains, I’ll just eat more vegetables.”

But in real life that’s usually not what happens.

More often, a very low-grain diet leads to:

- energy dips and fatigue

- stronger cravings (especially later in the day)

- overcompensation with protein, dairy, or fat (because the meal doesn’t feel satisfying)

I see this all the time: someone goes “low carb,” feels tired, gets hungry quickly, and ends up grazing on cheese, meat, and snacks instead of extra vegetables.

Whole grains deserve a bigger role (and better education)

If we want nutrition advice that works for most people, we should be focusing less on “cutting carbs” and more on upgrading carbs.

High-fiber whole grains include:

- oats

- quinoa

- barley

- brown rice

- farro

- bulgur

- whole wheat pasta

I understand that whole grains can feel intimidating if you didn’t grow up eating them, or if you don’t know how to cook them.

That’s why education matters just as much as the guidelines.

The USDA’s own messaging has long promoted making “half your grains whole”.

Different bodies have different carb needs

One of the biggest problems with one-size-fits-all food recommendations is that it ignores real-life differences.

An athlete doing intense training will have different carbohydrate needs than:

- a teen going through growth spurts

- a pregnant person

- a menopausal woman

- someone with blood sugar issues

This is exactly why I believe nutrition should be personalized. If the guideline is “less grains,” the next step should be: How much less? For who? Under what circumstances? That requires a conversation with a Registered Dietitian like myself.

Easy ways to add whole grains without “eating a ton of carbs”

Small, consistent upgrades can make a big difference.

Here are easy swaps I recommend as a registered dietitian:

- Swap white bread for 100% whole grain bread (same portion, more fiber)

- Use whole wheat pasta (start with ½ whole wheat + ½ regular if you’re picky)

- Choose oats at breakfast (oatmeal or overnight oats = easy fiber win)

- Add ½–¾ cup cooked quinoa or brown rice to meals

- Make “grain + veggie” bowls (¾ cup grain + 1–2 cups veggies + protein)

- Try high-fiber grains that feel “lighter”: farro, barley, bulgur (chewier, more satisfying = you often eat less)

- Use whole grains as a base layer, not the whole meal

- example: taco bowl with ½–¾ cup brown rice, beans, salsa, avocado, lettuce

- Swap crackers/chips for whole-grain crackers or air-popped popcorn

- Choose higher-fiber cereal occasionally (look for over 5g fiber per serving) and pair with protein

Bottom line: When grains are pushed too low, people often end up with less fiber, less energy, and less balance overall. Whole grains can be a simple, affordable way to support digestion, fullness, and long-term health.

Concern #5. Alcohol Guidance Is Too Vague

If the goal of national nutrition guidance is to Keep America Healthy, alcohol deserves clearer guardrails.

Why “drink less” isn’t a guideline

In the updated messaging, alcohol guidance essentially comes down to: drink less.

The new guidance emphasizes that less alcohol is better for health, but it doesn’t clearly define a cutoff. For context, the CDC defines moderate drinking as up to 2 drinks per day for men and 1 drink per day for women.

The problem is, that “drink less” is not really a guideline. It’s so open-ended that people are left to interpret what “less” means based on their own habits or what feels normal in their friend group.

And in the U.S., alcohol is incredibly normalized:

- happy hours

- “wine o’clock” culture

- drinking at celebrations

- drinking as stress relief

- and the idea that alcohol is a “social lubricant”

That last part is in the new dietary guidelines and is the most concerning to me. There is no clear amount highlighted, leaving someone to guess what “less” really means. When alcohol is framed as something harmless and socially necessary, it downplays the reality: alcohol has health effects, especially when intake becomes regular.

So if the pyramid is going to include alcohol messaging at all, it should be clear.

Finally, normalize “non-alcohol” choices without making people feel awkward:

- sparkling water with lime in a wine glass

- mocktails (seltzer + citrus + mint)

- iced herbal teas

- a “special drink” ritual that isn’t alcohol-based

Concern #6. Restriction Isn’t the Answer

This is something that I feel strongly about as a dietitian:

The answer is not more rules.

Yes, it’s helpful to encourage more whole foods and less highly processed foods. But when national nutrition messaging starts to sound like “never eat this” or “cut out that,” it can create the exact opposite effect of what we want.

Eliminating foods often backfires

Strict food rules tend to backfire.

When foods are labeled as “bad” or “off limits,” it often leads to:

- increased cravings

- guilt when someone eats the “wrong” thing

- overeating later (because restriction builds pressure)

- and in some cases, disordered eating patterns or thoughts

This is what I mean when I say restriction creates all-or-nothing thinking:

- “I was good today.”

- “I messed up, so I might as well keep eating.”

- “I’ll start over Monday.”

That mindset isn’t healthy and it’s not sustainable.

Nutrition should be something you can keep doing long-term. Because in a healthy lifestyle, consistency beats perfection every time.

A sustainable diet leaves room for enjoyment

Food is more than fuel.

Food is culture. Food is family. Food is celebration.

If the message becomes too rigid, people lose joy around eating. And that’s not what life is supposed to feel like.

This is why I always come back to this example:

Would we tell a 7-year-old she should never have ice cream at her birthday party?

Of course not.

Because we all understand that a treat does not ruin a child’s health and one cookie or one scoop of ice cream doesn’t ruin an adult’s either.

Health isn’t built by one meal. It’s built over time. And it’s definitely not made or broken by a single meal.

The real solution is education (not fear-based rules)

This is the missing piece in the United States: practical nutrition education.

Telling people what to eat is easy. Teaching them how to make choices in real life, in real grocery stores, with real schedules and budgets is where the impact is.

People need skills like:

- how to shop smart

- how to build a simple meal structure

- portion guidance that feels realistic

- label reading (without obsession)

- how to plan ahead without spending hours meal prepping

When restriction is encouraged, it creates extremes:

- people swing from one diet trend to the next

- they don’t know who to trust

- they assume healthy eating must be perfect to “count”

Honestly? We need more nutrition education in grade school so kids grow into adults who understand what will fuel and power them and how to build balanced meals without fear.

We need Registered Dietitians in grade schools and communities teaching the basics of nutrition and healthy eating in a way that’s clear, realistic, and supportive.

All Foods Fit (what that actually means)

When I say “all foods fit, I mean:

- whole foods as the foundation

- “fun foods” included intentionally (not daily mindless habits, but not forbidden)

- balance beats perfection

That’s how you get a healthier relationship with food and that’s how people actually change for the long term.

Concern #7. Why Aren’t Fruits & Vegetables the Foundation?

This is one of my biggest questions about the updated food guide pyramid:

If we want to improve health in the U.S., why aren’t fruits and vegetables the clear foundation?

When you look at the chronic health issues we’re trying to prevent like high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes, it’s hard to justify a nutrition model where vegetables don’t have the strongest visual emphasis.

If there’s one “common sense” strategy that improves almost everything, it’s eating more plants.

What I’d like to see emphasized more

If the pyramid is meant to guide the public, I’d rather see a stronger push toward this simple goal:

- At least 5 servings of vegetables per day

- 2–3 servings of fruit per day

Why? Because vegetables and fruit are some of the most powerful whole foods we have for:

- improving fiber intake

- supporting gut health

- helping with fullness and weight management

- lowering blood pressure

- reducing long-term heart risk

This is also why eating patterns like the DASH diet (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) and the Mediterranean diet are so strongly supported. They emphasize fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lower-fat dairy, which is directly tied to better blood pressure and heart health outcomes.

Implementation matters: education + practical support

Even if the guidelines say “eat more vegetables,” that message doesn’t automatically change behavior.

Telling people what to eat isn’t enough.

To actually help people eat more fruits and vegetables, we need practical support:

- how to shop (especially on a budget)

- what to buy if you don’t cook often

- how to prep veggies quickly without wasting food

- easy meal ideas that work for families

- realistic strategies for busy schedules

This is exactly why nutrition education matters so much.

If the guideline is “eat more produce,” the next step should be: Here’s how to make that doable in real life.

People don’t fail at healthy eating due to lack of willpower, they struggle because no one taught them the skills to make it simple and sustainable.

I want national guidance from registered dietitians to support a realistic way to build meals around whole food, starting with plants. If the new guidelines leave you feeling confused or frustrated, you’re not alone. In my 1:1 work, I help people simplify nutrition and create an approach that works in real life. Fill out my contact form here and I’ll follow up with next steps.

What I Recommend Instead: MyPlate

If the goal is to help the average person eat healthier in real life, MyPlate is still the better tool.

I’m not saying that based on opinion alone.

As a Registered Dietitian, I’ve spent decades helping people turn nutrition science into everyday meals, especially those juggling busy schedules, tight budgets, health concerns, and confusing food rules.

Why MyPlate works better for real life

MyPlate works because it does something the pyramid model struggles to do: it shows balance.

MyPlate encourages a healthy eating pattern across all the major food groups without implying that you should load up on one category more than the others. It also gives built-in structure with portion guidance people can understand at a glance.

In other words, MyPlate supports behavior change in the real world because it’s:

- balanced

- simple

- A clear visual

- flexible

- and doable for the average person

That matters because national guidelines need clarity. If people can’t apply the guidance, it doesn’t improve health.

The “MyPlate upgrade” I wish the guidelines pushed harder

If I could adjust the messaging to better reflect what we see in modern nutrition research and what I see in my private practice, here’s what I’d push harder:

- MORE vegetables (this is where most people are falling short)

- MORE plant proteins (beans, lentils, tofu/tempeh, nuts, seeds)

- LESS red meat, butter, and tallow as daily staples

That doesn’t mean “never.” It means not the foundation, and definitely not “eat more of this” messaging.

When animal fats dominate daily eating, saturated fat intake climbs quickly and we have decades of evidence showing that consistently high saturated fat intake raises LDL cholesterol, increasing cardiovascular risk.

So yes, I’m contradicting the interpretation some people are taking from the pyramid graphic and I’m doing it because it’s my job as an RD to prioritize scientific integrity and long-term health outcomes over politics and trends.

Build-your-plate examples

Here are two plates I recommend often because they work in real life.

1) Mediterranean-style plate (heart-friendly + satisfying)

½ plate: veggies (salad, roasted vegetables, sautéed greens)

¼ plate: protein (salmon, tuna, sardines, chickpeas, lentils, chicken)

¼ plate: whole grain or starchy veg (quinoa, brown rice, farro, sweet potato)

Healthy fats: olive oil, olives, avocado, nuts/seeds

Why it works: high fiber, high nutrients, great for heart health.

2) Budget-friendly plate (simple staples that still support health)

½ plate: frozen or fresh vegetables (stir-fry mix, broccoli, green beans)

¼ plate: protein (eggs, canned tuna, beans, lentils, chicken thighs)

¼ plate: affordable carbs (brown rice, oats, whole wheat pasta, potatoes)

Healthy fats: peanut butter, avocado oil, sunflower seeds

Why it works: this doesn’t require expensive “wellness foods.” It’s practical and sustainable.

If there’s one takeaway here, it’s this: You don’t need extreme guidelines to eat well. You need a framework that helps you build balanced meals over and over again and MyPlate does that better than any pyramid ever has.

Should You Follow the Updated Dietary Guidelines for Americans?

This is the question most people really want answered.

And my honest response is: don’t follow it blindly. Use it as a reference, not a rulebook.

The updated food guide pyramid can be a starting point for thinking about food choices, but it’s not the best tool for building a balanced diet. It’s easy to misread. And the visual is too busy without a clear sense of direction with regards to portion guidance.

If you want to use it, here’s how I would approach it.

What to take from it

There are a few messages in the new pyramid that I can support. In fact, these are the same basics I repeat with clients every week:

1) Eat more whole foods.

This is the most helpful takeaway. Focus on meals built around minimally processed ingredients.

2) Reduce ultra-processed foods and added sugars.

Many ultra-processed foods are high in refined carbohydrates, added sugars, and sodium. Cutting back can improve energy, cravings, blood sugar stability, and overall health.

3) Eat more fiber and plants.

Fiber is one of the biggest missing pieces in the average American diet, and it’s closely tied to gut health, fullness, blood sugar regulation, and heart health.

This is why I’m always encouraging more vegetables, beans, lentils, fruit, nuts, seeds, and whole grains.

Those are solid takeaways.

Final Takeaway: Use Common Sense

You need balance, consistency, and education.

The truth is, most people don’t struggle because they “don’t care.” They struggle because nutrition advice has become confusing, extreme, and often unrealistic. A graphic can’t tell you what your body needs, what your lifestyle allows, or what works for your health goals.

And if the new pyramid makes you feel confused or restricted, you’re not alone.

That’s why I recommend using MyPlate as your baseline. It’s balanced, flexible, and far easier to apply in real life. From there, you can personalize based on your goals, preferences, medical needs, and schedule.

The best eating plan isn’t the strictest one, it’s the one you can stick with.

Want help making this simple?

As a Registered Dietitian, I work with people who want a customized plan that fits real life. Together, we’ll build a way of eating that supports your health goals while still leaving room for enjoyment and flexibility.

Reach out to schedule a complimentary discovery call, and we’ll talk through what you need and what will work best for you.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Updated Nutrition Policy

1) Is 1.2–1.6 g/kg protein necessary for everyone?

No. That range may be helpful for certain groups (athletes doing intense training, older adults working to preserve muscle, or specific medical situations), but it’s not necessary for the average adult.

For most people, a more realistic and sustainable target is closer to 1.0 g/kg/day, especially if your goal is overall health, weight management, and balanced nutrition.

The bigger issue is this: if you’re pushing protein too high, you often crowd out other important foods like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and fiber.

2) Is full-fat dairy better than low-fat dairy?

It depends, but for most people, low-fat is the sweet spot.

Full-fat dairy has more saturated fat, which can be an issue if you’re already eating red meat, butter, and other saturated fat sources.

My recommendation:

- If someone has elevated cholesterol, heart disease risk, or is trying to manage weight → low-fat dairy is often the better everyday option.

- Full-fat dairy can absolutely fit in moderation, but it shouldn’t be the default for everyone

- fat helps promote satiety, which is a good thing – again in moderation.

3) Are carbs really causing weight gain?

Carbs don’t automatically cause weight gain.

Weight gain happens when your overall intake consistently exceeds what your body needs and that can come from any macronutrient (carbs, fat, or protein).

Also, not all carbs are the same:

- Whole grains, beans, fruit, and starchy vegetables provide fiber and nutrients

- Sugary drinks, pastries, and refined snacks are easier to overeat and don’t keep you full

So the issue isn’t carbs. It’s usually carb quality, fiber intake, portion sizes, and overall consistency.

We need to focus more on FIBER than vilifying carbs. Fiber is really the key for the general population.

4) What’s the healthiest oil?

For everyday use, extra virgin olive oil is one of the best-supported choices for heart health.

Other good options:

- Avocado oil (especially for higher heat cooking)

- Walnut oil can also be a reasonable option for some people although it’s not suited for cooking at high temperatures

The goal is to emphasize unsaturated fats more often, and limit high saturated fat oils like coconut oil and animal fats as daily staples.

5) What does “processed” mean?

“Processed” isn’t always bad.

Processing can mean something as simple as:

- frozen vegetables

- canned beans

- plain yogurt

- oats

- bagged salad

Those are processed and they can be very healthy.

The bigger concern is ultra-processed foods, which typically contain:

- lots of added sugar

- refined starches

- seed oils in large amounts

- additives/flavor enhancers

- very low fiber and nutrients

Bottom line: Processed foods aren’t the enemy. Highly/ultra-processed foods are the ones we want to limit most of the time.

6) What should kids eat if sweets are “removed”?

I don’t recommend “removing sweets”, especially for children.

When sweets are treated like forbidden food, it often makes them more exciting, and can create guilt, obsession, or sneaking behavior and can lead to disordered thoughts and eating.

A healthier approach is:

- teach moderation

- keep sweets as “sometimes foods”

- focus on nutritious daily habits (regular meals, fruits/veg, protein, whole grains)

Kids should be able to enjoy birthday cake or ice cream at a party because that’s normal life.

7) What’s the simplest version of a healthy diet?

If you want the simplest, most realistic version:

Build balanced meals most of the time:

- ½ plate vegetables (more vegetables) + fruit

- ¼ plate protein (preferably plant-forward more often)

- ¼ plate whole grains or starchy vegetables

- Add in healthy fats (olive oil, nuts, seeds, avocado)

Then leave room for flexibility because the healthiest eating pattern is the one you can sustain.